Hydrogen drive is considered the most serious option for achieving zero-emission rail transport. The challenge is to provide green rolling stock on lines served by diesel engines. In Poland, this is more than one third of railway routes. Experts predict that it will take a few more years before such trains will appear in our country. However, the direction of change seems to be inevitable, especially as more and more countries are choosing this type of drive and testing or investing in hydrogen-powered locomotives. Market analysts also predict that interest in such vehicles will grow dynamically. Between 2025 and 2035, the market value of these vehicles is expected to increase tenfold.

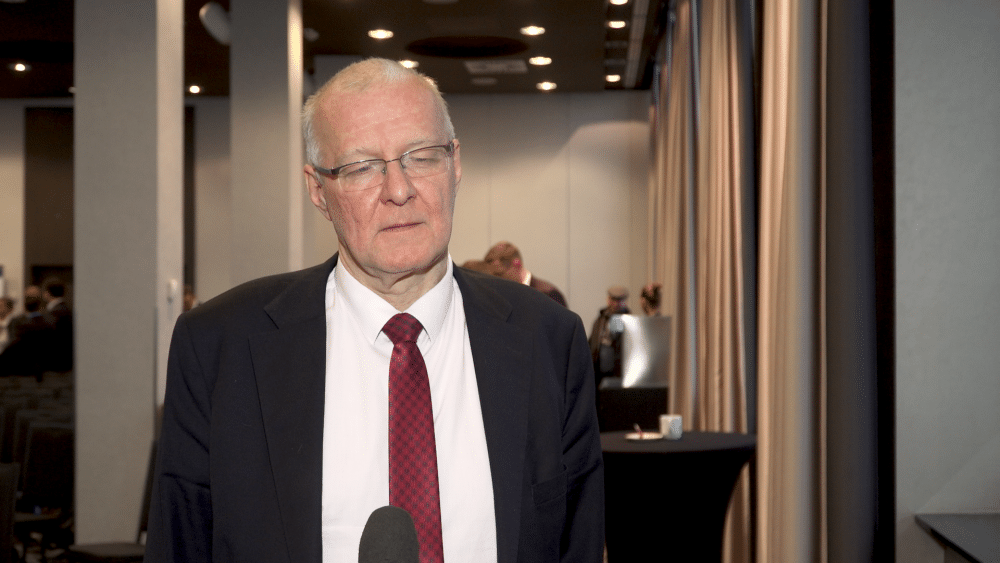

“There are individual examples of hydrogen train operation, for example in Germany, in Lower Saxony, but it is still a kind of test operation, i.e. the trains are running, but it is still clear that this is a very expensive technology and until it reaches a certain scale, it is difficult to talk about reducing the price of hydrogen vehicles or hydrogen refuelling stations,” commented Dr. Andrzej Massel, Director of the Railway Institute, in an interview with Newseria Innovation agency.

Hydrogen locomotives are primarily an alternative for those powered by fuel, i.e., serving non-electrified lines. An example could be the recent contract signed by Stadler to deliver six hydrogen-powered trains for the US state of California. In total, the fleet is expected to have nine sets.

Data from the Railway Transport Office indicates that non-electrified lines account for over 37% in Poland.

“There are parts of the network where there is no overhead line and one of the solutions that can be considered is the use of hydrogen drive. There are various areas of hydrogen application in rail transport, one possibility is also the use of hydrogen vehicles for the service of sidings, i.e. large industrial plants, a lot of manoeuvring, in such conditions a refuelling station can provide power to locomotives moving in the area of a given plant or railway node,” the expert points out.

The shift away from diesel drive directly results from EU regulations, which envisage moving away from traditional fuels in favour of sustainable transport. Although hydrogen power is one of the most seriously considered options, it is not without its drawbacks. The main one, especially for passenger and freight transport, is the cost of hydrogen-powered vehicles. This can be even twice as high as that of diesel vehicles. There are also frequently raised doubts related to safety, especially in situations where there is a risk of hydrogen leakage, e.g. during refuelling. Contact with oxygen causes an explosive reaction.

Another challenge is infrastructure, and, finally, hydrogen production. Conversion will only make sense when green hydrogen is produced and its price is low enough to be a relatively cheap fuel. The number of challenges to be faced encourages market participants to also consider other options for providing zero-emission transport.

“Under certain conditions, hydrogen vehicles can be replaced by electric vehicles with additional batteries, allowing for the crossing of non-electrified sections. Everything depends on the specific operating conditions of a given railway line. If there is a non-electrified section of several dozen kilometers in length, a battery-powered vehicle is sufficient, and on longer sections – 150-200 km – hydrogen technology seems to be best suited,” points out Dr. Andrzej Massel.

According to Allied Market Research, the global market for trains powered by hydrogen fuel cells will reach revenues of $2.67 billion in 2025. By 2035, this is expected to be $26.41 billion.