At least 44% of Poles have supported at least one false health-related claim, according to a study by GfK conducted last year for the Digital Poland Foundation. The health sector is one of the most common motifs in fake news, a phenomenon that has strongly intensified especially during the COVID-19 pandemic and remains present. Fighting it is challenging as false information, like viruses, quickly and easily spreads online. Only about 5% of Poles use fact-checking services to verify information. Importantly, young people who trust social media and are not able to distinguish truth from falsehood are more susceptible to pseudoscientific theories and fake news.

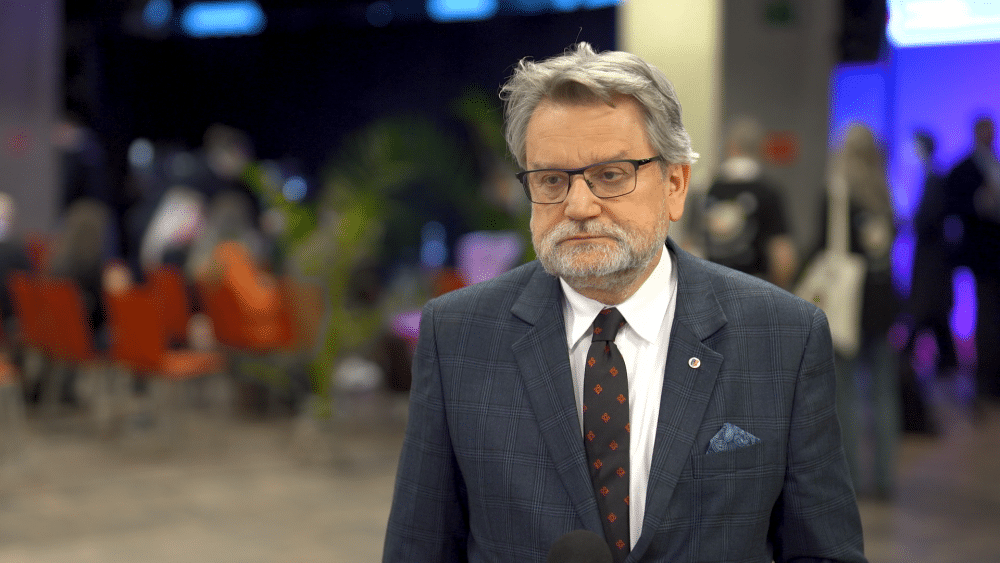

“Medical fake news is a huge problem. It can lead to human tragedies, sometimes even death, as it influences our poor health choices. We behave irrationally because we’re indoctrinated, it seems to us that what we’re told is the only right thing, and that’s a big mistake,” says Prof. Jarosław Pinkas, director of the Public Health School of the CMKP, and a national consultant in public health.

The 2020 report by Digital Poland reveals that 61% of Poles derive their knowledge from online sources like info portals, 45% from social media, 42% from search engines, and 30% read online blogs and forums . On the other hand, the internet and social media are one of the main sources of fake news – encountered by as many as 82% of Poles. In the GfK report, over half of the respondents (51%) said they encountered fake news on social media. About one-third mentioned blogs and forums (32%), and one in five pointed to online portals (27%). Interestingly, 13% of respondents reported encountering fake news even on specialized online services. The most common topics for false news are climate and energy, but health is also a frequent subject.

“The most common false news relate to topics we search for online, such as vaccines, diet, or how to deal with various types of diseases,” says Prof. Pinkas. For example, when someone searches on how to deal with a cold, they may encounter misleading information about a product that’s being promoted for sale, serving as a form of product marketing rather than effective health advice.

According to 63% of Poles, manufacturers hide information about harmful ingredients or food additives. 57% believe that genetically modified plants are unhealthy for humans. There are also false theories about vaccines and pandemics – one-third of Poles believe the pandemic was pre-planned, 19% believe Bill Gates is behind it, and 13% agree with the theory that vaccines cause autism and that SARS, swine flu, and COVID-19 are the result of deploying 3G, 4G, and 5G technologies.

Fake news is mainly created by denialists who reject true knowledge, says Prof. Pinkas. They are not created by medical professionals or scientists, but by people who aim to profit from ignorance by promoting harmful ideas. Dealing with this is hard because people often don’t realize the intent behind it and struggle to verify what they see online.

Particularly susceptible to pseudoscientific theories and fake news are people living in rural areas, those with a lower education, those using so-called “alternative” sources of information, and most notably, young people who trust social media and couldn’t tell fact from fiction. For instance, in the 18-34 age group, 42% believe the COVID-19 pandemic was pre-planned. Among older people aged 55+, only 19% believe this theory.

“The phenomenon of medical fake news is very dangerous as it often spreads faster than the most contagious virus,” emphasizes Prof. Pinkas. This is confirmed by a 2018 study by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) which proved that it takes fake news on Twitter on average six times less time to reach 1,500 people than true information, and has a higher chance of being retweeted.

The phenomenon has particularly intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic, with a flood of misleading information about the virus spreading online. The virus has become a perfect tool for internet trolls and cybercriminals aiming to benefit from the situation. This was termed “infodemic,” to reflect the explosive spread of both the virus and fake news.

The pandemic has led to a situation where we increasingly search for information online as direct contacts with professionals were limited. This resulted in people often coming across misleading information, says Prof. Pinkas. Only 5% of Poles use fact-checking services according to the GfK survey, and even Big Tech despite declarations of combating the spread of false information, is not doing enough.

The problem is also that social media users often unconsciously or consciously become a channel for spreading fake news further. NASK (National Research Institute) studies from 2019 show that nearly one in five respondents admitted to sharing or liking information on social media which they knew was false.

“We should trust medical professionals and be capable of finding good information from a variety of proven sources like research institutes or trusted institutions based on scientific evidence,” concludes Prof. Pinkas.